By Natalie Fidlow, CFA

New York City’s multistory industrial projects have surged over the past five to seven years; however, slower leasing activity has raised questions about the viability of this model. This week at the I.CON East conference in Jersey City, New Jersey, industry experts shared the projects that are succeeding and the innovative approaches they are developing in the urban industrial sector. Scot Murdoch, AIA, partner at KSS Architects, moderated a panel discussion on how to deliver both economic and community benefits.

Stephen Kim, director of design and development at Innovo Property Group, LLC, spoke about the successes and lessons learned from several multistory spaces, including The Borden Complex. This five-story Long Island City development integrates distribution, light manufacturing, film and TV studios, and office spaces, forming a hub for creative production. Having a studio with dressing rooms located on top of a warehouse was out of the box, said Kim, but it worked.

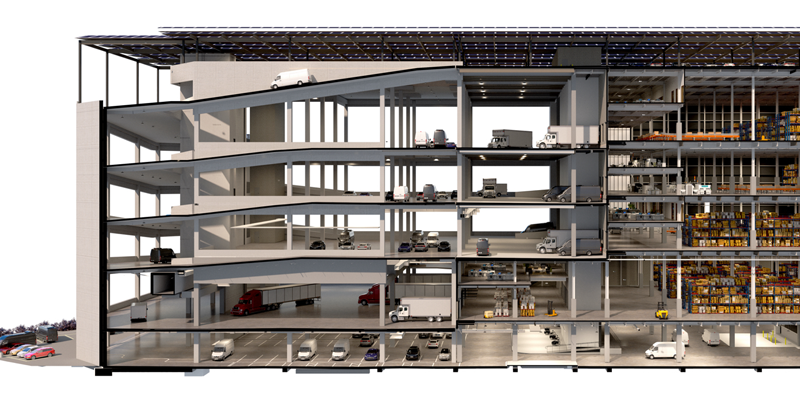

By the time his firm built the Review Ave Complex, Kim knew that he needed to build for flexibility in both users and uses. This former brownfield site located near public transit combines single-story warehouse efficiency with a six-story vertical design. “Every floor is a first floor with a lobby. There are four levels of warehouse, with parking,” Kim explained.

Michael Bennett, LEED AP, vice president and head of development at DH Property Holdings LLC, shared his firm’s multistory lessons from their projects. At 640 Columbia Street, the first two floors act as first floors for each tenant’s truck service and the third floor is a warehouse. During the course of the project they learned that there were significantly more trucks than anticipated, and the project required substantially more parking.

A subsequent project, Sunset Industrial Park, consists of 27 tenants on 18 acres. The positives of this space were that it had multiple access points along various streets. “If a tenant had a lot of trucks, we could plan for other tenants to enter through a different point of entry,” Bennett said. They tailored the spaces to include fleet services, cold storage and distribution. It also has water barge potential. They were able to retain existing large clients, such as FedEx and Verizon, by working with them to address their specific needs.

A member of the audience asked what metrics help to justify a multilevel project. Kim answered, “Construction costs and land availability.” Bennett added, “The cost per square foot for a one-story versus a four-story is the same in the New York City area. So, if we want to maximize land use, multistory is a way to do that.”

Jon Siani, AIA, NCARB, director of development at Prologis, hit on one theme that’s universal to all cities: “They are super focused on lowering trucks and congestion.” In particular, he highlighted New York City’s vision for a “blue highway” that uses the city’s waterways for transporting goods and reduces reliance on road-based freight. Prologis is working toward making that vision a reality.

Operationally, Siani explained that the trailers would be transported to a New Jersey site by the water. They would unhitch onto floating ferries and distribute to hubs in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Pier 92, and/or the Navy Yard. There, they would be delivered to consumers and microhubs, where employees could deliver goods off-hours on e-bikes.

At this stage, the neighborhood of Bayonne is a pilot project for this model. Another neighborhood, Greenpoint, is a case study. The Brooklyn Navy Yard is one of the few sites that is ready to serve as a hub today.

An adjacent interest in New York is micromobility. “The city is trying to get trucks off the street,” Siani explained.

It’s an exciting time in this space. Siani concluded, “Coming out of [the COVID-19 pandemic], never has there been more attention to getting trucks off the roads. With that comes investor and community interest.”

Murdoch mentioned that now many cities mandate that developers do not try to dismantle a community and instead attempt to “understand unforeseen consequences.” He asked Ed Klimek, AIA, partner emeritus at KSS Architects, how the firm accounts for local context.

In the planning phase, local context is critical in urban planning. There is an emphasis on production [in the U.S.], and not just in manufacturing but in producing items that are sometimes unique to a city,” Klimek said, citing film production as an example.

Planning for urban industry requires considering development according to three zones.

First, there’s integrated industrial development, consisting of 5,000- to 30,000-square-foot units in the neighborhood and existing industry. The National Manufacturing Association conducted a study indicating that 80% of American manufacturing is performed by firms with fewer than 20 employees, which allows firms to scale and increase production. For example, Klimek points to Ralph Lauren – the company found it easier to manufacture some refined clothing domestically. These locations have storefronts and are part of the neighborhood.

Second, there is emergent industrial development aimed at fostering innovation and new technologies, such as life sciences and robotics. Being around cities, with think tanks and universities, is advantageous. These facilities range in size from 50,000 to 100,000 square feet and are essential for companies that require research laboratories. It solves the problem that pharmaceutical companies face when they start in the U.S. but must relocate production abroad as they scale. Brownfields can lend themselves well to this type of development.

Lastly, there is regional industrial development with facilities that offer multistory opportunities. Distribution, production, commercial and public use can all be included in these large buildings. Klimek highlighted Philadelphia as a good locale for this type of development, as 25% of all produce that is shipped into the U.S. comes through Philadelphia. They now have a competitive advantage with packaging and storing food, but land is scarce. Possible multistory features could include ghost kitchens and greenhouses on roofs. Places like Philadelphia are production ecosystems, which Klimek maintains are more important now because firms can scale at a smaller level.

Klimek says they look at what zone works in each local context. “We are not designing for industry; we are designing for the city.”

Photo source: Review Avenue Complex

This post is brought to you by JLL, the social media and conference blog sponsor of NAIOP’s I.CON East 2025. Learn more about JLL at www.us.jll.com or www.jll.ca.